Farming Phosphorus: When Growing Life Hurts

This image was taken by European Space Agency’s Copernicus Sentinel-3 on 15 March 2020, showing the extent of algal blooms, turbid waters, and other water quality issues in the Great Lakes. Sentinel-3 is an environmental monitoring mission with two satellites that, among other things, track color changes on the Earth’s surface. Credit: ESA/Copernicus Sentinel-3 – Image contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data (2020), processed by ESA, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO.

A pungent layer of goop the color of guacamole spreads across a lake, closing beaches, killing wildlife, and poisoning drinking water. It sounds like the beginning of an old comic book series, but it’s the reality of millions of people worldwide. These harmful algal blooms (HABs) are a product of excess intricately tied to climate change, modern industrial agriculture, and a lack of effective pollution oversight. HABs are found nationwide, from small inland ponds to the Great Lakes. Even Lake Superior’s famous crystal waters have been affected lately. But it's especially bad in Lake Erie.

Green muck from an intense harmful algal bloom (HAB) in 2011 sticks to the side of a dock in Lake Erie. Credit: Jeff Reutter/Ohio Sea Grant (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Lake Erie, the shallowest and warmest of all the Great Lakes, is dotted with cities like Toledo and Cleveland in Ohio, Erie in Pennsylvania, and Buffalo in New York. Its watershed houses seventeen major metropolitan areas, providing drinking water to eleven million people. When one of the worst blooms in recent history occurred in the summer of 2014, Toledo banned its residents from drinking tap water for three days. And while large cities can contribute to water pollution, crops and animals from surrounding farmland are far and away the main contributors to the mucky problem of HABs.

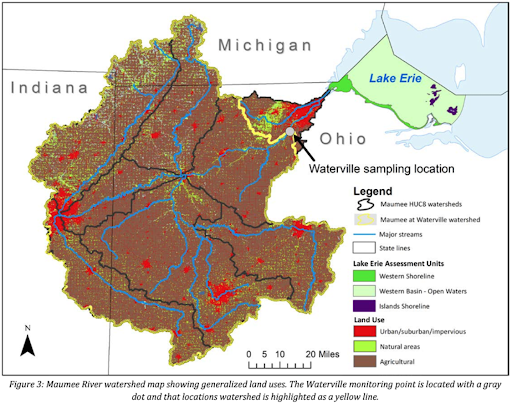

Maumee River watershed map showing generalized land uses. Credit: Ohio EPA

Take the Maumee River, for example. It is one of Lake Erie’s main tributaries and its largest watershed, supplying the lake’s shallow western basin with about 1.6 trillion gallons of water per year from a 6,600 square-mile area. According to a 2016 report led by the University of Michigan, approximately 85 percent of the phosphorus entering the lake through this river originates on farms in the form of fertilizer and manure runoff. But what does phosphorus have to do with harmful algae?

Understanding the Role of Phosphorus

Over the last several decades, research has confirmed (sometimes famously) the position of phosphorus as the primary fuel for freshwater HABs. On some level, this makes sense. Phosphorus is an essential element for all life, giving structure to DNA, cells, and entire bodies for those with teeth and bones. Part of the natural phosphorus cycle includes being eliminated from living beings through waste, specifically in urine and feces, as well as decomposition. And although we didn’t necessarily know why, humans have known of manure’s almost magical effects on soil health and crop growth for millennia.

But throughout the 1800s, our understanding of soil chemistry evolved, spurring a boom in fertilizers. This knowledge allowed more crops to be grown to feed ever-expanding populations. And while we no longer raid battlefields for bones or rely on often deadly colonial exploitation of guano islands, we do mine the Earth heavily for phosphorus to include in chemical fertilizers used around the world. But if we only used fertilizer on crops used for human consumption, we wouldn’t have nearly the same problems with freshwater HABs that we do today. The major culprits? In the US, anyway, it’s corn and cows.

Domestic corn use has grown over the decades due mostly to the United States’ commitment to ethanol. 12 billion bushels is the equivalent of about 672 billion pounds. Credit: USDA/ERS

What happens when cows eat corn?

According to the USDA, the United States is the world’s largest producer, consumer, and exporter of corn. We plant about 90 million acres every year in what’s known as the Heartland of the US, a region including the Great Plains and a few additional states. Of the 600-some billion pounds of corn we use annually, only 15 percent is processed for human consumption - and over half of that is high fructose corn syrup or artificial sweeteners. (Just one percent of all corn grown in the US is sweet corn, the kind we eat straight from the cob.) The other 85 percent is mostly designated for ethanol - now considered a net carbon emitter - or animal feed - of which corn is used almost exclusively. And when farm animals eat hundreds of billions of pounds of corn, hundreds of billions of pounds of manure tend to be the result.

A 2019 joint investigation from the Environmental Working Group and the Environmental Law & Policy Center found that, between 2005 and 2018, the number of animals within the Maumee watershed grew by over 225 percent. Toledo’s Mayor even told a local newspaper these concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) “produce the manure equivalent of human waste generated by the cities of Chicago and Los Angeles combined.” Of course, it’s important to note that human waste is treated before entering the waterways; animal waste is not. Today, approximately 10,600 tons of phosphorus is added to the watershed annually from manure alone - a veritable feast for the organisms producing HABs.

In 2008, an important study was published analyzing the economic impact that human-induced eutrophication - excess nutrients that cause things like HABs - may have on US waterways. At the time, it said it gave a conservative estimate of $2.2 billion-$4.6 billion of annual economic harm, but expected that number to rise if fertilizer use continued to increase. Since 2008, though, our landscape has literally changed. Corn use has grown significantly; animal farms have largely consolidated, concentrating the impacts of tens of thousands of animals' waste in single areas; and the amount and severity of freshwater HABs in the US has risen in response. What can be done to prevent further harm to our ecosystem as well as billions of dollars of lost annual revenue? Legislate.

What to do?

Every five years, congress reevaluates national programs related to agriculture and food in an omnibus bill called the Farm Bill. The next Farm Bill, which is being created this year, is a critical opportunity for Congress to advance legislation that will protect the Great Lakes, enhance water quality across the watershed, address the threat of toxic algal blooms, invest in community development, infrastructure, and public health, and support the implementation of sustainable farming practices and alternative cropping systems.

The Healing Our Waters-Great Lakes Coalition believes that, at a minimum, Congress must:

Double Farm Bill Conservation Funding to no less than $12 billion, ensuring the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and its conservation programs are fully funded and staffed to provide training, technical assistance, monitoring, and support for the implementation of sustainable conservation practices.

Reform the Federal Crop Insurance Program (FCIP) by providing incentives for the implementation of soil health practices, diversified and regenerative agriculture, and establishing conservation planning and compliance as a requirement for qualification.

Require the development of water-quality based standards to reduce agricultural runoff, tying funding through conservation and other major assistance programs to the long-term implementation of best practices for clean water outcomes.

The Great Lakes region is a major agricultural center, but that shouldn’t come at a great cost to water quality and public health.